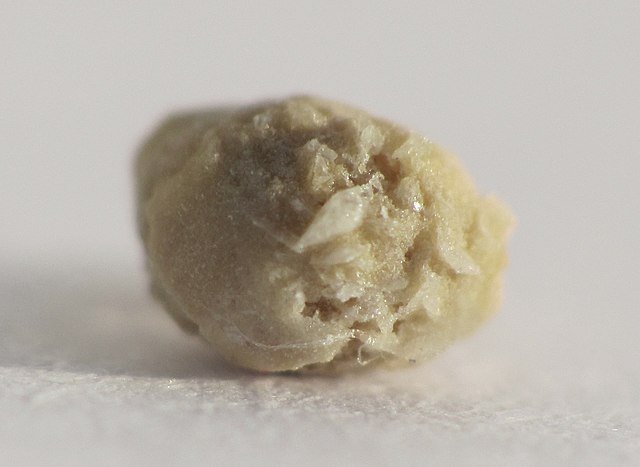

Kidney stones are hard masses that can grow from crystals forming within the kidneys. Doctors call kidney stones “renal calculi,” and the condition of having such stones “nephrolithiasis.”

Most kidney stones are made of calcium oxalate. People with a history of kidney stone formation should talk with their doctor to learn what type of stones they have— approximately one stone in three is made of something other than calcium oxalate and one in five contains little if any calcium in any form. Calcium oxalate stone formation is rare in primitive societies, suggesting that this condition is preventable. People who have formed a calcium oxalate stone are at high risk of forming another kidney stone.

Caution: The information included in this article pertains to prevention of calcium oxalate kidney stone recurrence only—not to other kidney stones or to the treatment of acute disease. The term “kidney stone” will refer only to calcium oxalate stones. However, information regarding how natural substances affect urinary levels of calcium may also be important for people with a history of calcium phosphate stones.

What are the symptoms of kidney stones?

Kidney stones often cause severe back or flank pain, which may radiate down to the groin region. Sometimes kidney stones are accompanied by gastrointestinal symptoms, chills, fever, and blood in urine.

Dietary changes that may be helpful

Increasing dietary oxalate can lead to an increase in urinary oxalate excretion. Increased urinary oxalate increases the risk of stone formation. As a result, most doctors agree that kidney stone formers should reduce their intake of oxalate from food as a way to reduce urinary oxalate. Many foods contain oxalate; however, only a few—spinach, rhubarb, beet greens, nuts, chocolate, tea, bran, almonds, peanuts, and strawberries—appear to significantly increase urinary oxalate levels.

Increased levels of urinary calcium also increases the risk of stone formation. Consumption of animal protein from meat, dairy, poultry, or fish increases urinary calcium. Perhaps for this reason, consumption of animal protein has been linked to an increased risk of forming stones and vegetarians have been reported to be at lower risk for stone formation in some reports. As a result, many researchers and some doctors believe that people with a history of kidney stone formation should restrict intake of animal foods high in protein.

In one controlled trial, contrary to expectations, after 4.5 years of follow-up, those who restricted their dietary protein actually had an increased risk of forming a kidney stone, compared with the control group. The findings of this trial conflict with the outcomes of most preliminary studies, and need to be confirmed by further clinical trials.

Other researchers have found that a low-protein diet reduces the risk of forming stones. Although high-protein diets should probably be avoided by people with kidney stones, the effect of restricting dietary protein to low levels (below the RDA level of 0.8 grams per 2.2 pounds of body weight per day) remains unclear. Until more is known, it makes sense to consume a diet with a moderate amount of protein, perhaps partially limiting animal protein, but not limiting protein from vegetarian sources, such as nuts and beans.

Salt increases urinary calcium excretion in stone formers. In theory, this should increase the risk of forming a stone. As a result, some researchers have suggested that reducing dietary salt may be a useful way to decrease the chance of forming additional stones. Increasing dietary salt has also affected a variety of other risk factors in ways that suggest an increased chance of kidney stone formation. Some doctors recommend that people with a history of kidney stones reduce salt intake. To what extent such a dietary change would reduce the risk of stone recurrence remains unclear.

Potassium reduces urinary calcium excretion, and people who eat high amounts of dietary potassium appear to be at low risk of forming kidney stones. Most kidney stone research involving potassium supplementation uses the form potassium citrate. When a group of stone formers was given 5 grams of potassium citrate three times daily in addition to their regular drug treatment for 28 months, they had a significantly lower rate of stone recurrence compared to those taking potassium for only eight months and to those taking no potassium at all.

Although citrate itself may lower the risk of stone recurrence (see below), in some potassium research, a significant decrease in urinary calcium occurs even in the absence of added citrate. This finding suggests that increasing potassium itself may reduce the risk of kidney stone recurrence. The best way to increase potassium is to eat fruits and vegetables. The level of potassium in food is much higher than the small amounts found in supplements.

Some citrate research conducted with people who have a history of kidney stones involves supplementation with a combination of potassium citrate and magnesium citrate. In one double-blind trial, the recurrence rate of kidney stones dropped from 64% to 13% for those receiving high amounts of both supplements.

In that trial, people were instructed to take six pills per day—enough potassium citrate to provide 1,600 mg of potassium and enough magnesium citrate to provide 500 mg of magnesium. Both placebo and citrate groups were also advised to restrict salt, sugar, animal protein, and foods rich in oxalate. Other trials have also shown that potassium and magnesium citrate supplementation reduces kidney stone recurrences.

Citric acid (citrate) is found in many foods and may also protect against kidney stone formation. The best food source commonly available is citrus fruits, particularly lemons. One preliminary trial found that drinking 2 litres (approximately 2 quarts) of lemonade per day improved the quality of the urine in ways that are associated with kidney stone prevention. Lemonade was far more effective in modifying these urinary parameters than orange juice. The lemonade was made by mixing 4 oz lemon juice with enough water to make 2 litres. The smallest amount of sweetener possible should be added to make the taste acceptable. Further study is necessary to determine if lemonade can prevent recurrence of kidney stones.

Drinking grapefruit juice has been linked to an increased risk of kidney stones in two large studies. Whether grapefruit juice actually causes kidney stone recurrence or is merely associated with something else that increases risks remains unclear; some doctors suggest that people with a history of stones should restrict grapefruit juice intake until more is known.

Bran, a rich source of insoluble fibre, reduces the absorption of calcium, which in turn causes urinary calcium to fall. In one trial, risk of forming kidney stones was significantly reduced simply by adding one-half ounce of rice bran per day to the diet. Oat and wheat bran are also good sources of insoluble fibre and are available in natural food stores and supermarkets. Before supplementing with bran, however, people should check with a doctor, because some people—even a few with kidney stones—don’t absorb enough calcium. For those people, supplementing with bran might deprive them of much-needed calcium.

People who form kidney stones have been reported to process sugar abnormally. Sugar has also been reported to increase urinary oxalate, and in some reports, urinary calcium as well. As a result, some doctors recommend that people who form stones avoid sugar. To what extent, if any, such a dietary change decreased the risk of stone recurrence has not been studied and remains unclear.

Drinking water increases the volume of urine. In the process, substances that form kidney stones are diluted, reducing the risk of kidney stone recurrence. For this reason, people with a history of kidney stones should drink at least two quarts per day. It is particularly important that people in hot climates increase their fluid intake to reduce their risk.

Drinking coffee or other caffeine-containing beverages increases urinary calcium. Long- term caffeine consumers are reported to have an increased risk of osteoporosis, suggesting that the increase in urinary calcium caused by caffeine consumption may be significant. However, coffee consists mostly of water, and increasing water consumption is known to reduce the risk of forming a kidney stone. While many doctors are concerned about the possible negative effects of caffeine consumption in people with a history of kidney stones, preliminary studies in both men and women have found that coffee and tea consumption is actually associated with a reduced risk of forming a kidney stone.

These reports suggest that the helpful effect of consuming more water by drinking coffee or tea may compensate for the theoretically harmful effect that caffeine has in elevating urinary calcium. Therefore, the bulk of current research suggests that it is not important for kidney stone formers to avoid coffee and tea.

The findings of some but not all studies suggest that consumption of soft drinks may increase the risk of forming a kidney stone. The phosphoric acid found in these beverages is thought to affect calcium metabolism in ways that might increase kidney stone recurrence risk.

Nutritional supplements that may be helpful

IP-6 (inositol hexaphosphate, also called phytic acid) reduces urinary calcium levels and may reduce the risk of forming a kidney stone. In one trial, 120 mg per day of IP-6 for 15 days significantly reduced the formation of calcium oxalate crystals in the urine of people with a history of kidney stone formation.

In the past, doctors have sometimes recommended that people with a history of kidney stones restrict calcium intake because a higher calcium intake increases the amount of calcium in urine. However, calcium (from supplements or food) binds to oxalate in the gut before either can be absorbed, thus interfering with the absorption of oxalate.

When oxalate is not absorbed, it cannot be excreted in urine. The resulting decrease in urinary oxalate actually reduces the risk of stone formation, and the reduction in urinary oxalate appears to outweigh the increase in urinary calcium. In clinical studies, people who consumed more calcium in the diet were reported to have a lower risk of forming kidney stones than people who consume less calcium.

However, while dietary calcium has been linked to reduction in the risk of forming stones, calcium supplements have been associated with an increased risk in a large study of American nurses. The researchers who conducted this trial speculate that the difference in effects between dietary and supplemental calcium resulted from differences in timing of calcium consumption.

Dietary calcium is eaten with food, and so it can then block absorption of oxalates that may be present at the same meal. In the study of American nurses, however, most supplemental calcium was consumed apart from food. Calcium taken without food will increase urinary calcium, thus increasing the risk of forming stones; but calcium taken without food cannot reduce the absorption of oxalate from food consumed at a different time. For this reason, these researchers speculate that calcium supplements were linked to increased risk because they were taken between meals. Thus, calcium supplements may be beneficial for many stone formers, as dietary calcium appears to be, but only if taken with meals.

When doctors recommend calcium supplements to stone formers, they often suggest 800 mg per day in the form of calcium citrate or calcium citrate malate, taken with meals. Citrate helps reduce the risk of forming a stone (see “Dietary changes that may be helpful” above). Calcium citrate has been shown to increase urinary citrate in stone formers, which may act as protection against an increase in urinary calcium resulting from absorption of calcium from the supplement.

Despite the fact that calcium supplementation taken with meals may be helpful for some, people with a history of kidney stone formation should not take calcium supplements without the supervision of a healthcare professional. Although the increase in urinary calcium caused by calcium supplements can be mild or even temporary, some stone formers show a potentially dangerous increase in urinary calcium following calcium supplementation; this may, in turn, increase the risk of stone formation.

People who are “hyperabsorbers” of calcium should not take supplemental calcium until more is known. Using a protocol established years ago in the Journal of Urology, 24-hour urinary calcium studies conducted both with and without calcium supplementation determine which stone formers are calcium “hyperabsorbers.” Any healthcare practitioner can order this simple test.

Increased blood levels of vitamin D are found in some kidney stone formers, according to some, but not all, research. Until more is known, kidney stone formers should take vitamin D supplements only after consulting a doctor.

Both magnesium and vitamin B6 are used by the body to convert oxalate into other substances. Vitamin B6 deficiency leads to an increase in kidney stones as a result of elevated urinary oxalate. Vitamin B6 is also known to reduce elevated urinary oxalate in some stone formers who are not necessarily B6 deficient.

Years ago, the Merck Manual recommended 100–200 mg of vitamin B6 and 200 mg of magnesium per day for some kidney stone formers with elevated urinary oxalate. Most trials have shown that supplementing with magnesium and/or vitamin B6 significantly lowers the risk of forming kidney stones. Results have varied from only a slight reduction in recurrences75 to a greater than 90% decrease in recurrences.

Optimal supplemental levels of vitamin B6 and magnesium for people with kidney stones remain unknown. Some doctors advise 200–400 mg per day of magnesium. While the effective intake of vitamin B6 appears to be as low as 10–50 mg per day, certain people with elevated urinary oxalate may require much higher amounts, and therefore require medical supervision. In some cases, as much as 1,000 mg of vitamin B6 per day (a potentially toxic level) has been used successfully.

Doctors who do advocate use of magnesium for people with a history of stone formation generally suggest the use of magnesium citrate because citrate itself reduces kidney stone recurrences. As with calcium supplementation, it appears important to take magnesium with meals in order for it to reduce kidney stone risks by lowering urinary oxalate.

It has been suggested that people who form kidney stones should avoid vitamin C supplements, because vitamin C can convert into oxalate and increase urinary oxalate. Initially, these concerns were questioned because the vitamin C was converted to oxalate after urine had left the body. However, newer trials have shown that as little as 1 gram of vitamin C per day can increase urinary oxalate levels in some people, even those without a history of kidney stones.

In one case report, a young man who ingested 8 grams per day of vitamin C had a dramatic increase in urinary oxalate excretion, resulting in calcium-oxalate crystal formation and blood in the urine. On the other hand, in preliminary studies performed on large populations, high intake of vitamin C was associated with no change in the risk of forming a kidney stone in women, and with a reduced risk in men.

This research suggests that routine restriction of vitamin C to prevent stone formation is unwarranted. However, until more is known, people with a history of kidney stones should consult a doctor before taking large amounts (1 gram or more per day) of supplemental vitamin C.

Chondroitin sulphate may play a role in reducing the risk of kidney stone formation. One trial found 60 mg per day of glycosamionoglycans significantly lowered urinary oxalate levels in stone formers. Chondroitin sulphate is a type of glycosaminoglycan. A decrease in urinary oxalate levels should reduce the risk of stone formation.

In a double-blind trial, supplementation with 200 IU of synthetic vitamin E per day was found to reduce several risk factors for kidney stone formation in people with elevated levels of urinary oxalate.

Herbs that may be helpful

Two trials from Thailand reported that eating pumpkin seeds reduces urinary risk factors for forming kidney stones. One of those trials, which studied the effects of pumpkin seeds on indicators of the risk of stone formation in children, used 60 mg per 2.2 pounds of body weight—the equivalent of only a fraction of an ounce per day for an adult. The active constituents of pumpkin seeds responsible for this action have not been identified.

Photo by Jacek Proszyk